Sukrita Paul Kumar

Conversation with Usha Akella (Oct 2023)

In this interview with Usha Akella, Sukrita Paul Kumar shares her poetics while conversing about her new book of selected poetry, Salt & Pepper, published by Poetrywala, India (2023).

A lot of my poetry comes out of meditation not on exile but on roots.

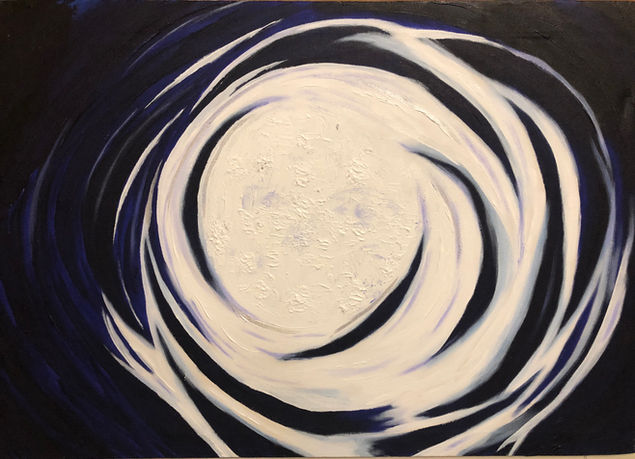

Born and brought up in Kenya, Sukrita Paul Kumar is an eminent poet, noted translator, painter and critic with numerous achievements in the literary field. Briefly, by way of introduction, she held the Aruna Asaf Ali Chair at the University of Delhi. Currently she lives in Delhi and is the Guest Editor, Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi. An Honorary Fellow of the prestigious International Writing Programme, University of Iowa (USA), of Cambridge Seminars and a former Fellow of the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla, she was also an invited poet in residence at Hong Kong Baptist University, China. She represented India as a poet at the BRICS Literary Summit held in China in 2018. Honorary faculty at the Durrell Centre at Corfu (Greece) and a recipient of many international fellowships and residencies, she has published several collections of poems in English that include , , and(with Yasmin Ladha). As Director of a UNESCO project on “The Culture of Peace”, she edited , a volume of Urdu short stories from India and Pakistan. Her two bilingual collections are (with Hindustani translations by Gulzar) and (with Hindi translations by Savita Singh). Sukrita’s major critical works include "Narrating Partition" and "The New Story". Some of her edited/co-edited books include "Speaking for Herself"(Penguin), "Mapping Memories"(Katha), "Krishna Sobti: A Counter Archive "(Routledge).

A number of Sukrita’s poems have emerged from her experience of working with homeless people, Tsunami victims and street children.

Usha: Sukrita, Congratulations on your new book of selected poems Salt and Pepper! I loved every minute of reading your nuanced and fragile poetry, astonishing as well, like the poems in the book Fire of Meaning. I was compelled to quote several lines in this interview to share the beauty of your poetry with readers (as a result, I may have invented a new genre of review-interview, ‘intereview’!). Thank you.

Coincidentally, even before I read your introduction, I began to wonder about how a poet selects poems for a selected works-kind-of-volume. I then saw that you had addressed this in your introduction, you suggest that one must learn to become a reader of one’s poems. Can you elaborate on that?

Sukrita: Many thanks, dear Usha for your warm response to my book of selected poems, Salt & Pepper. Perhaps “collected works/poems” type of a book is easier but having to choose poems for a “selected poems” volume is what causes problems. What criteria do you work out for yourself for the selection? I thought let me chronologically arrange all my poetry and then pick poems from each period historically. Interestingly, I discovered that some of the poems I have in the first section could well have been written in more recent times. For instance, the one that seems to have resonated with you, “A Borrowed Existence”, is one of my earliest poems. Normally we think we evolve as poets over time but such an understanding gets defied when many a good poem may belong to an earlier phase…while some written much later appear to be pretentious dolls, well crafted but hollow as poetry. Moreover, it is very easy to get attached to your own poems because each one triggers some personal memory. One has to develop an aesthetics of forgetting -so to speak- to read your own poems in their autonomy without the associative personal memories. This detachment is necessary to be able to become a “reader” of your own poems, especially while making a selection for others who may in turn develop their own personal reasons/memories to respond to them. The poem needs to be stripped of the implied personal associations of the poet for it to be allowed to wear the new apparel offered by each reader’s sensibility.

Usha: I think that’s not easy, stripping the poem of its associative history that perhaps initiated the poem in the first place. In that case, what were your criteria that made a poem qualify? What is a good poem in your estimate?

Sukrita: Well, for one, “the stripping of associative history” is easier if the poem is an earlier poem. The time lapse in itself helps remove the immediacy of a memory which gets replaced by the poem’s autonomy that generates new associations, not of history but of the present times perhaps. In that the poem takes you to newer associative contexts of words, metaphors and symbols, taking you away from the narrow domain of a specific personal memory that imprisons the poem within a narrow frame. Also, the alertness about the need to see the poem from within its own being can help perhaps.

You ask: what is a good poem? Simply one that has open entry and exit points, and does not just argue an issue or a point towards a definitive conclusion. In a good poem, the words chosen are almost magical in their capacity to be inclusive of different meanings; there is a healthy ambivalence, a questioning of the status quo, a lyrical flow even while depicting turbulence. A good poem is not exhibitionism, nor macho in its display of verbal muscles. It throbs with commitment to exploration rather than declaration of a truth that can even be overturned in the same poem. But the seeking continues …along with a strong sense of beauty yielded by style, tone etc. If I may say so, to me the aesthetics of a poem must have an underlying sense of ‘good intent’ even if to arouse compassion, empathy or love. Rooted deep in reality -social or personal-, poetry flies high with wings of imagination. A good poem is always transformative…that much for the impact!

Usha: This sounds almost like a Yin-Yang or Shiva-Shakti poetics!

Homing in poetry and painting; a lot of my poetry comes out of meditation not on exile but on roots. These two statements struck me in your introduction—please share your thoughts on poetry as domicile, your interesting use of the verb form: homing—implying ‘home’ in reality is not a noun or even a destination.

Sukrita: To me “homing” is a process, different from arriving at a destination that is home. This is a continuum of the experience that carries within its folds the idea of continuous transiting…there is no finality of arrival there. While the ending of each poem may offer rest, it also suggests a halt, a breather or a pause as if preparing one to commence on the next part of the journey. This also carries within itself the idea of a search for home. The concept of home then gets to be elusive. Reaching the ending of a poem may indicate arrival but soon it becomes clear that the end actually immediately calls for another beginning. The movement is not linear but cyclic…From poem to poem! Poetry as the final destination would mean the end of the poetic journey. In that the poet is indeed condemned to remain homeless throughout!

Usha: Aphoristic stanzas, and pithy poetic lines surface in your work frequently. In some sense, one could say brevity allows for the suggestive power of poetry, inviting the reader to participate…Comment?

As in:

Children play

with toys

adults with their

conscience (from ‘Little Ones’)

*

Dreams sink like paper-boats

when belief sits in them

*

Words are stones

when in exile

*

Sukrita: As for the creative process behind such writing, I feel there is a storm, a bountiful of words raining from different planes of consciousness, jostling to somehow get into a poem. Clever, impressive and sometimes unusually polite words -smartly attired- do tend to place themselves in the centre of the poem even when they are not required. It is a challenge to ward them off … and a tremendous amount of creative constraint is needed to leave them out since they “look” so good. But only superficially so. One has to ruthlessly shunt them out. In fact, only a bare minimum of them is required to make poetry in a poem. The bare minimum means stripping the extra attire off…that’s when begins the process of sifting and churning so as to keep what has to stay compellingly. I have become very conscious of this process over time and I have realized how extraordinarily attentive one has to remain to receive, and not lose, flashes of insights that may descend on one without any notice. They are the ones that serve as beacon lights, amidst the creative journey. Yes, to me brevity matters hugely…I keep trimming my poems, of words that hang around loosely. You are so right, the reader too needs to find ways of participation in the poem and if the poem is suggestive in its meaning/s the reader gets more engaged in it.

Usha: The courage to be simple!

Your voice bespeaks of acute self-awareness. It feels like the reader is eavesdropping on the musings of your innermost being. Your poems radiate out of your core from an interior space with the universe embedded in it—Self and ‘other’ transpose and dissolve. This sense of osmosis is something unique, and done beautifully in your poetics. Comment.

As in:

As my eyes tailed

the sparrow

building a nest

straw by straw

I became a mother

of three chicks

*

the sand dunes of the

desert

spread their grainy presence

in my memory

*

Snakes

waking and

rising

out of

my

soul

*

The garden blossomed

in winter

because

I died in spring

*

I feel my ghost/ Uneasy in my body (‘Blue Baby’)

*

Passage

Each moment

I shed

my loneliness

like

the oaks shed

their leaves

and

like the oaks

I feel

at once

the pangs

of

new sprouts

*

Another

Confronting

sharks and whales

I ventured

to sail

far out

into the seas

till you

emerged from

the fathomless

blues

…a survivor…

Sukrita: You know what Usha, I feel, rather than self-awareness, I really carry the weight of just acute awareness…I would like to believe that I shed my “self” while I slip into the mode of writing a poem. Something impersonal takes over or should I say that another self, not that of an individual per se, but it could be any and every self, even that of a tree. I too feel as though I am eavesdropping and I struggle to capture the musings I hear from within in a poem. I may or may not decipher the interpretation of what emerges in the form of a poem. Sometimes it may be also a little baffling when I seem to be led into a tunnel waiting for some light to move forward…You put it so beautifully when you refer to an interior space where the Self and “other” meld into an osmosis. Thank you for helping me understand this feature a bit. The creative process remains forever so confusing and mysterious!

I love the lines you have picked up from my poetry to illustrate your explanation. There is no definitive poetics that I follow consciously. However, I do seem to be consciously condensing the expression which in turn makes the poem suggestive of multiple meanings. Note the following:

The dew drop swallows

the sun

and leads a colourful existence

*

When my shadow

Overtook me

I knew

I had crossed the sun

*

Or then, here’s one from the series “We the Homeless”:

Saabji,

Said the boy from Badayun,

Teach me to write a letter,

A letter that my old Ma can read,

She never went to school, Saabji!

And remember, Saabji,

I won’t learn to write

what she can’t read!

Usha: One word came to mind as I read through your poems- sacred—you remind us the Self is a sacred space, and poetry is a sacred, and generous art that invites readers into its confines. Comment.

Sukrita: I can only say that I regard poetry, in fact any activity that can be termed art, to be an honest attempt to be utterly and ruthlessly truthful. One may fail in one’s efforts but in the sincere and committed effort itself there lies poetry. To get a glimpse of that is inspiration. It’s after getting that inspiration that the struggle to make it to some truth begins through the process of writing a poem. That involves labour, sheer labour! The tools of vocabulary, form, style etc., have to be handled very astutely. “Sacredness” lies in the purity of intention and pursuance of truth, no matter how much the sweat and labour. No compromise and no pedantry. And it’s blasphemous to lose the focus. The readers join in to explore what the poet may have triggered in the poem that stretches and expands in its range of meanings with the involvement of each new sensibility. Poetry is indeed generous in accommodating countless number of true and serious readers…

To me, the following lines demonstrate the sacredness of a girl who cannot speak:

She is a statue

with tell-tale eyes

that hold back

restive oceans

Usha: Thank you for the joy of your poetry Sukrita; truly I looked forward each day to reading your poems. And I know I will return to them again. I wish you continue to enrich Indian poetry with your fine sensibility.

Sukrita: I am grateful Usha to have you resonate with the poems so well. The most rewarding experience of creating poetry is to have reached some hearts that absorb the poems as their own across time and space. It’s like co-creation of the poems…in this the so-called “original” are merely points of take-off. With genuine readers, the poems may extend in the range of their meaning and get totally transformed as they are received by each of the readers… that would indeed depend on the power and destiny of the poem as much as the catholicity of the reader’s mind and imagination, don’t you think?

Thanks ever so much for this conversation.

Usha: Thank you sincerely!